Rackham made his living as an illustrator for 47 years, and worked on dozens of books, but Rip Van Winkle, his first artistic and commercial success, was not published until 1905, when he was almost 40.

The story of Arthur Rackham's career is one of steady progress. He attended the Lambeth School of Art part time while working a day job as a clerk, then went on to work as an illustrator for a paper called the Pall Mall Budget, then switched to the (equally dull-sounding) Westminster Budget.

"...for the next seven years or so I worked as hard as I could out of business hours (9–5) to equip myself as an artist – not being able to embark on a professional career till I was nearly 25, & then for many years getting the barest living from my profession & having to do much distasteful hack work."

-Derek Hudson, Arthur Rackham, His Life and Work

For the most part, the work he did for these papers had little to distinguish it from the mass of utilitarian Victorian news illustrations generated before photography rendered them obsolete– but inklings of his future work could be seen in drawings such as "The Influenza Fiend."

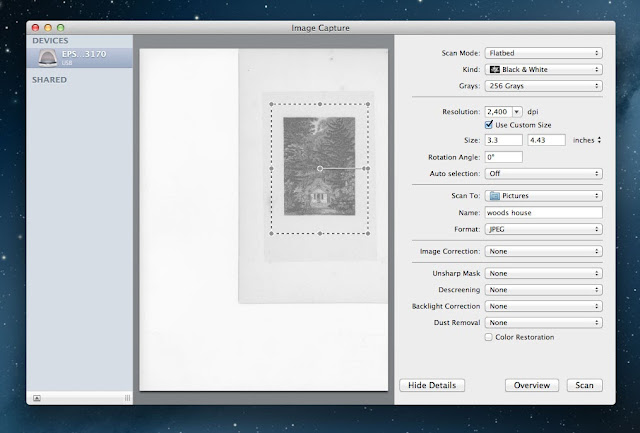

Rackham worked at a time when printers were switching from woodblocks to the photo zinc process. Where previously the engraver would often reinterpret the artist's original lines to suit his own style or tools– sometimes gluing the original artwork directly to the woodblock as a template– this new process allowed the work to be reproduced identically, and left original drawings unharmed. This is meaningful, as the sale of original artwork was an important source of income throughout Rackham's career.

In contrast to the fairy tale worlds he drew, Rackham led a fairly conventional life. He was a Luddite and a family man, by all accounts happily married to his wife, Edyth, whose own paintings were well recognized in her time. Their studios were next to each other, and some credit her with helping him introduce color to his work.

His particular working method is described in Fred Gettings' 1975 biography, Arthur Rackham:

"Rackham would begin his pictures by sketching carefully with a soft pencil the broad outlines of the composition either working on card, or on a good quality, slightly textured, paper mounted on card… into this he would work his figures or emotive points of interest. This method of working– from established mass to to details within the mass– remained with Rackham throughout his life."

"…into the general mass of the pencil drawing he would then work in pen and indian ink, and once the basis of the drawing had begun to emerge in ink, he cleaned off the pencil drawing beneath..."

He finished with an allover wash of color (usually sepia), then gradually intensified the colors with thin layers of watercolor– never gouache, as was commonly used at the time. Any lines which were washed out in this process he would trace once more with ink to keep them crisp in reproductions. He started out working at twice the intended reproduction size, and then started working a little larger as he earned more income from selling originals.

Rackham brought his fanciful style to a broad range of subjects. He illustrated operas by Wagner, and plays by Shakespeare. He cultivated a friendship with J.M. Barrie while working on Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. He even illustrated an early edition of Goblin Market, a poem so loaded with erotic symbolism that it was reprinted in Playboy in 1973.

It is a testament to how well-regarded Rackham was in his day that he was asked to illustrate new editions of The Wind in the Willows and Alice in Wonderland– two books which were already quite well known for their illustrations.

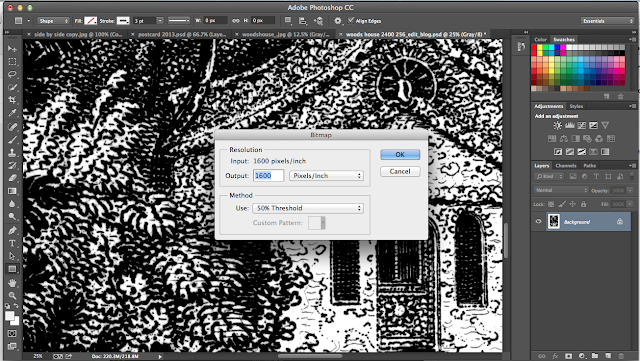

Some of the illustrations he originally published in black and white were later republished in color. But you can see here how the color is not necessary for definition of the subject- the linework stands quite well on its own.

Part of the difficulty in researching his work was that many of his illustrations were oversaturated for reprints or the web; it is difficult to find digital images which faithfully reproduce his intended hues.

Sales of fine illustrated books lagged in England after WWI, but in the US, the market was booming. And luckily, his original artwork continued to sell briskly despite England's economic malaise.

Rackham worked at the peak of his ability right up until his death in 1939. He finished the illustrations for Wind in the Willows while suffering from cancer, driven in part by his lingering regret over having had to turn down the project 20 years prior.

Derek Hudson's book contains this lovely anecdote:

"Slowly the drawings for The Wind in the Willows neared completion. The last drawing of all to be finished was that of Rat and Mole loading their boat for a picnic. Rackham's daughter remembers his great exhaustion and the extreme difficulty he had in getting it done. When he had, as he thought, finished it, he suddenly discovered there were no oars in the boat. Barbara (His daughter) tried to persuade him that this was a detail that did not matter, but he insisted that everything must be right, and with great labour he altered the drawing and put in the oars. After he had done this, he lay back on his bed and said: 'thank goodness, that is the last one'. And so it proved in every sense."